A Reverse Perfect Manhattan From 1895

An easy-to-make, low-ABV sipper that dials back the sweetness.

It’s still January, so let’s keep things light and simple with an easy-to-make, cold-weather friendly, low-proof, old-school Manhattan variation that will help you think about ways to dial back a cocktail’s sweetness.

One of the easiest ways to build a lower-proof cocktail is to take something in the Manhattan or Martini family—drinks that tend to revolve around two ounces of higher-proof base spirit and a single ounce of vermouth or other low-proof, flavorful modifier—and flip the proportions. Instead of two ounces of whiskey or gin, use two-ish ounces of vermouth, and half the base spirit.

Flipping the proportions gives you simple but tasty drinks like the Astoria (essentially a reverse Martini) and the Reverse Manhattan (self-explanatory).

Martinis and Manhattans in this style are inherently sweeter than their un-reversed counterparts. That’s especially true with Manhattans, thanks to the higher sugar content of sweet vermouth.

When you “reverse” a Manhattan, you’re doubling the volume of the sweet element in the drink (vermouth) while paring back the unsweetened element (whiskey).

For some people, that’s just too sweet. I often enjoy Reverse Manhattans, but depending on the choice of vermouth and bitters, they can come across somewhat syrupy.

One way to mitigate the sweetness is to use a bitter vermouth like Punt e Mes. That makes for a truly delicious cocktail, but given that Punt e Mes is bittersweet in a way that drinks an awful lot like an amaro, you’re basically just reinventing the Boulevardier.

Which is not necessarily a problem, because the Boulevardier—essentially a Negroni with whiskey instead of gin—is a delicious cold-weather cocktail. Maybe you just want a Boulevardier? If you make it with Cynar, the proof comes in about the same as a Reverse Manhattan.

Or maybe you don’t want a Boulevardier, because you don’t like bittersweet, amaro-esque liqueurs like Cynar and Campari.

Yes, as perhaps the internet’s foremost un-sponsored Cynar enthusiast, I find this somewhat strange. But I know that many of my good friends, as well as some readers of this newsletter, feel this way.

In that case, I have another suggestion: Instead of a basic Reverse Manhattan, cut the sweet vermouth with dry vermouth for a Reverse Perfect Manhattan.

We looked at the Perfect Manhattan last year. And over the holidays I argued that the Boothby, which adds dry Champagne to the Manhattan template, was essentially a 50/50 Reverse Perfect Manhattan. Even still, I want to emphasize how far back this approach to drink-making goes.

This is not a new idea. This is not a new-this-century idea. It’s not even a new-last-century idea.

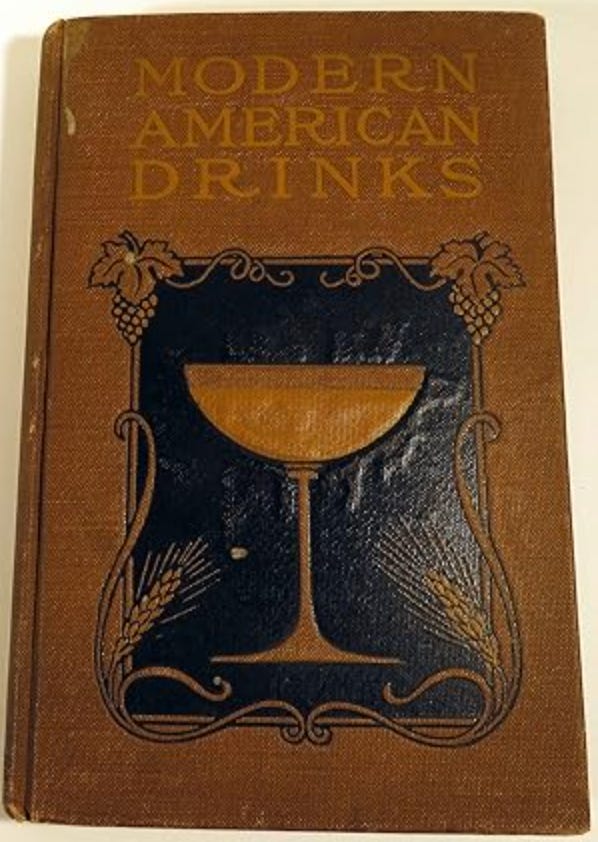

It dates back to at least 1895, when George J. Kappeler published his seminal cocktail manual, Modern American Drinks.

So this week, we’re going to discuss Reverse Manhattans and Perfect Manhattans. And then we’re going to make an often-overlooked cocktail using an essentially unchanged, unmodified recipe from Kappeler’s book.

It was delicious 130 years ago, and it’s still delicious today.

Sweet Child O’ Mine

Bartenders often get requests for drinks that are “not too sweet.” The truth is that nearly all cocktails involve some sort of sugar or sweetener, whether it’s in the form of sugar syrup or sweetened liqueur, like Luxardo Maraschino liqueur or Bénédictine.

Still, you have to manage that sweetness. There should be enough to counter-balance bitter or sour components, but not so much as to overwhelm the drink.

And one of the best ways to balance the sweetness of a cocktail is to look at what’s worked in other, similar drinks. If it’s worked before, it can work again.

As I have noted before, the Manhattan is essentially an Old Fashioned but with sweet vermouth replacing the teaspoon or so of sugar/sugar syrup that sweetens an Old Fashioned. Indeed, one ounce of sweet vermouth typically contains about a teaspoon of sugar—making it a pretty straightforward comp with an Old Fashioned. They are different drinks, yes, but functionally, they’re the same idea, and they balance the same way.

But if you cut the whiskey in half and double the sweetener, you suddenly have a very different balance.